John & Katharine Maltwood Collection

| View the Collection |

History of the Collection |

John & Katharine Maltwood |

Information Resources |

The Maltwoods Introduction

Katharine Maltwood Biography

Early Sculpture

Post-War Works Glastonbury Zodiac Life in Victoria, B.C. Monograph (pdf 1.14 MB)

About Us Contact Us Visit Us Site Map

Life in Victoria, B.C. | ||||||||||

In the gracious comfort of "The Thatch" the Maltwoods settled down to quietly live out the remainder of their lives. Katharine Maltwood enjoyed inviting local friends to tea, showing off her art treasures and explaining her discovery of the Somerset Zodiac. In addition, she was keen to continue her own artistic pursuits. For this purpose a north upper "studio room" was added to "The Thatch", recreating the artist's beloved retreat, the west tower of Chilton Priority. In this new workshop she produced several small sculptural pieces and experiemented with local materials. One of the first was The Hand of God which commemorated George VI's words "put your hand into the hand of God" in the Christmas Day speech of 1939. The clasped hands were modelled from those of Katharine Maltwood's god-daughter, Diana Holland, and emerge from an archaic, temple like form." Alabaster was one of her favourite mediums due to its translucent qualities and this work was carved from that of a local quarry at Falkland.74 It appears the sculptress also brought some alabaster with her from England. This was used in the shallow relief portrait, Vivat Rex, a profile of King George VI set off by shafts of sunlight.

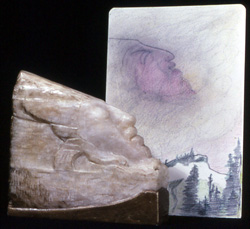

Katharine Maltwood was naturally interested in the art and culture of the northwest coast Indians. A small alabaster, Indian Head, dates from her early years in Victoria. This interest may also be the source of inspiration of The Fox Dance, a small relief carved in black slate from the Queen Charlotte Islands. The rough carvings of a primitive head and face show her experiments with soapstone as a possible mode of expression. Being now in her sixties, she had not the same strength in her hands as when younger as the modified technique of her Victoria works reveal. They tend to be smaller in scale, with fairly shallow carving and a preference for softer stones that allowed her to use her wood-carving tools.

During these years she turned increasingly to landscape sketching. The Maltwoods were particularly fond of country retreats. They purchased a small cottage at Cowichan Bay and also "Treetops", a property covering a high promontary in Cordova Bay, which they wished to preserve in its natural state. Here Katharine Maltwood loved to walk and sketch, being captivated by the views across the Strait of Georgia to the Coast Mountains of British Columbia, to the San Juan Islands with Mount Baker beyond, or south to the Olympic Mountains of Washington. Her pastel sketch series, Treetops, is filled with snow-capped peaks, standing silent and stark, beyond calm coastal waters. She sought to capture the dramatic atmospheric effects, the opaque reflections and the ever changing light, often giving a mystical, otherworldly impression. Colour was used sparingly; misty greys and blues are favoured highlighted with a suggestion of yellow, green or red. In contrast her tree studies are ablaze with rich fall colours, radiating with an inexplicable interior light that suggests her knowledge of Emily Carr's work. The forms are drawn sculpturally as though twisting with energy and movement. Katharine Maltwood's absorbing interest in the changing seasons and the rhythms of life made the arbutus tree especially intriguing. Among her forest interiors the arbutus predominates in burning colours and romantically noble forms such as "Victory for the Arbutus" and "Mists clothe the arbutus stems in Enchantments."

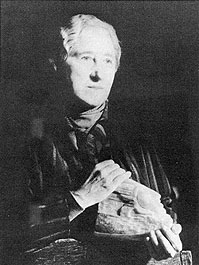

That her sculptures were as much concerned with the essence of nature as her landscape sketches is displayed in two unusual mountain scenes where an archaic head emerges from the face of a mountain. The features resemble precisely those of her alabaster carving, Indian Head. In her vision of this primitive face, moulded as if asleep for eternity in the rock, she implies the ultimate unity of all creation. The sketch books present an interesting reflection of Katharine Maltwood's feelings towards nature. She was inspired by the vastness, solitude and crystalline purity of the rugged British Columbia landscape. Her knowledge of Oriental thought and Theosophy gave her a deep sensitivity to nature's power and moral virtues. She believed that nature revealed the laws of God and, like the character Brynhild Ingmar, sought spiritual fulfilment through immersion in the vital forces of the land. Out in the wilds it seems she had a feeling of exhaltation and freedom of the senses; a pantheistic identity of spirit with nature and the universe. Katharine Maltwood was always a very vital and active personality and remained so even in her old age. However, in the 1950's she suffered the increasing disability of Parkinson's disease. She faced this distressing illness with great courage but was eventually forced to give up all her artistic pursuits. After a long and harrowing illness she died on July 29, 1961, leaving her work and collection to the people of British Columbia. In 1964 "The Thatch", its contents and an endowment were officially bequeathed to the University of Victoria. John Maltwood outlived his wife by several years, dying in his hundred and first year on June 18, 1967. The Maltwood Collection was moved from "The Thatch" to the University of Victoria in 1977. The move was granted after a hearing on a petition under the Administration Act to alter the Trust created in Katharine Maltwood's will.

In the establishment of a museum the artist wished to provide a place "for the encouragement of the study of the arts" and to perpetuate the ideals she had sought to fulfil in her own lifetime. Her quest was one of spiritual evolution and harmony with "higher, hidden realities". In this she remained very much a child of the Victorian era seeing modern society as being in a state of spiritual crisis and moral decline brought on by the trivialities of materialism, the "soulless mechanism" of technology and the decay of cultural traditions. As a result she sought a return to truth and beauty through art, surrounding herself with a nostalgically gracious and exotic environment that was distant from the prosaic experience of daily life. Although she appeared aloof and distant to lesser known acquaintances, to her closer friends she was a genius, kind, modest and noble in character. To John Maltwood, her devoted companion, "She was a remarkable, creative genius, perpetually young and vigorous, everything she did was perfect - she was a goddess."102 In her sculptural aspirations, philosophical leanings and in the immense significance she attached to her discovery of a pre-historic zodiac Katharine Maltwood took on the role of a visionary and an evangelist. Although her views and life-style appear somewhat remote from the commonplace, we can understand her concerns in that the crisis of man versus technology still remains, creating a common vein of idealism which links nineteenth and twentieth-century philosophies.

All content on this page is copyright © 30 January, 2006 |

||||||||||