An example of one of Spalding's advertisements as it appeared in a 1905 Souvenir Edition of the Fernie Free Press.

An example of one of Spalding's advertisements as it appeared in a 1905 Souvenir Edition of the Fernie Free Press.

Born in London in 1877, Joseph Frederick Spalding immigrated to Canada in 1898, possibly wooed by the same sort of images he would later spend a lifetime preserving in photographs. When he arrived in Fernie (collections.ic.gc.ca/fernie/) in March of 1904, the town of 1,400 residents had only recently been incorporated. Its rapid economic growth was based on the discovery of coal seams in the Elk Valley area, which subsequently brought both the railway and the logging industry to Fernie.

In 1898, the British Columbia Southern Railway, a subsidiary of the Canadian Pacific Railway, was constructed through the Elk Valley. Three years later, in 1901, the Crows Nest Southern Railway was built to connect the coal fields of the Elk Valley to the Great Northern Railway lines in Montana. Lumber was required for station houses, cattle guards, track maintenance in the mines, and for the construction of the town’s buildings. Fernie grew quickly as homes for the miners, coke ovens, and beehive ovens were built to handle the ten thousand tons of coal extracted each year. Business, to say the least, was booming.

Spalding's 1911 price listings.

Spalding's 1911 price listings.

Spalding became an active member of the burgeoning community, bringing with him a small personal photography enterprise he had founded in 1902. A number of photographers, including Steele & Co Ltd and A.W. Prest, had previously documented the early development of Fernie. When Prest was slowed by illness in 1905, Spalding took over his office and widely advertised to attract business. Spalding’s photographs were used extensively in the Fernie Free Press souvenir editions, and he claimed he was prepared to “do anything in the Photograph line and guarantee it all.” The souvenir editions documented local history and events, and promoted a community vying for new settlers.

In 1908, Spalding invested over $1000 to modernize his studio, furnishing it with new backdrops and accessories. Spalding’s ties to the community were strengthened when he, along with the other residents of Fernie, lost his home and business in the Great Fire later that year. Despite his own loss, Spalding relentlessly documented the eerie aftermath of the fire. Many of his photographs depict the charred remains of buildings against the ashen wasteland of what had been a thriving town, while tiny shadowed figures stare in amazement at the ruins.

Spalding officially announces his recent studio renovations.

Spalding officially announces his recent studio renovations.

Spalding was on-hand to chronicle the rebuilding of Fernie, and his photographs of the reconstruction convey the resilience of the townspeople. Remarkably, the city “rose from the ashes” within months. Photographs by Spalding of a bustling business area, the construction of new buildings, such as the law courts, and groups of residents gathered together at relief distribution centers illustrate the perseverance of Fernie’s citizens.

By 1910, the population of Fernie had boomed to 3,500 and the town boasted sawmills, curling and skating rinks, banks, hotels, and all the other amenities of a modern town. During this time, Spalding photographed fine houses, panoramic views of Victoria Avenue on snowy days, and residents dressed in finery strolling down the streets of Coal Creek. He also photographed working men: in the bush logging, heading into the mine tunnels, fishing on the Elk River, and working on the railway. Spalding’s numerous images of trains, mining operations and logging technology celebrate Victorian ideals of progress – the drive to conquer nature, to gain prosperity, and to secure technological advancement. Such notions were slow, however, to accommodate the consideration of labour strife, ethnic divisions (collections.ic.gc.ca/Kootenay/main/virt.asp), or poverty.

Spalding's 1907 work highlighted on behalf of the Elk Lumber Co. Ltd.

Spalding's 1907 work highlighted on behalf of the Elk Lumber Co. Ltd.

The cover of a pamphlet compiled by Spalding on behalf of the Tourist Association of Southern Alberta and Southeastern British Columbia.

The cover of a pamphlet compiled by Spalding on behalf of the Tourist Association of Southern Alberta and Southeastern British Columbia.

Fernie, as Spalding pictured it, was a boom town surrounded by picturesque scenery. Many of his images were recreated as postcards, thus allowing his photographs to reach across Canada and the world beyond. Spalding found further professional success with the Tourist Association of Southern Alberta and Southeastern British Columbia, and he used his experiences and photography to tout the area to tourists.

The cover and final page for Spalding’s Official Automobile Road Guide.

The cover and final page for Spalding’s Official Automobile Road Guide.

Although he left the Elk Valley in 1924, Spalding’s legacy in Fernie is incalculable since not only was he on hand to personally chronicle the town’s development in photographs, but in his role as Tourism Commissioner he encouraged the settlement of Fernie and outlying areas. From his correspondences and writings in the local press it is evident that he felt Fernie was full of potential. In a 1919 letter to the editor of the Fernie Free Press, he stated “we have absolutely the finest scenery there is in the whole of the North American continent…” Aside from the Great Fire of 1908 and the flood of 1916, his photographs present an idyllic location where new settlers might like to plant roots, and his numerous photographs of social events convey an attitude of progressive community spirit. Spalding believed in Fernie, and his photographs of the town impart his feelings of optimism for its future.

Joseph Frederick Spalding died in Vancouver, B.C., on February 11, 1958, predeceased by his wife Ida Merle in 1951.

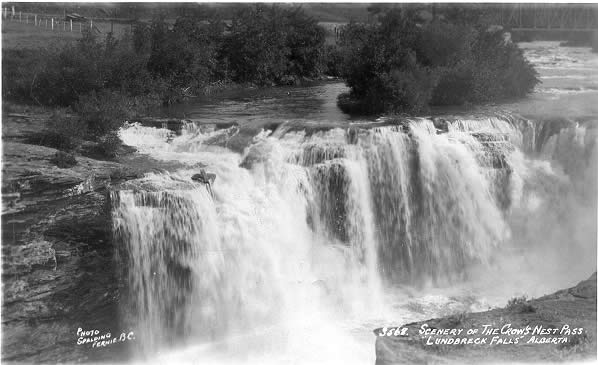

A simply breathtaking image of Lundbreck Falls in the Crowsnest Pass, Alberta.

A simply breathtaking image of Lundbreck Falls in the Crowsnest Pass, Alberta.

Copyright © 2004 Fernie and District Historical Society In cooperation with the Community-University Research Alliance