John & Katharine Maltwood Collection

| View the Collection |

History of the Collection |

John & Katharine Maltwood |

Information Resources |

The Maltwoods Introduction

Katharine Maltwood Biography

Early Sculpture

- Education - Magna Mater - London Salon (1912) - Primeval Canada - A Vision - Contemporary Style - Eric Gill Post-War Works Glastonbury Zodiac Life in Victoria, B.C. Monograph (pdf 1.14 MB)

About Us Contact Us Visit Us Site Map

Early Sculpture - Part 7: Eric Gill | ||

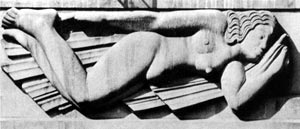

The most interesting comparison to Katharine Maltwood's art is found perhaps in the work and artistic outlook of Eric Gill. A stone carver, woodengraver, draughtsman and writer, Gill studied initially at Chichester Art School and was then apprenticed to an architect from 1900 to 1903. He became a figure sculptor in 1910 and among his most important commissions were The Stations of the Cross in Westminster Cathedral from 1918, the figures for London Underground Railways of 1929, and his works for Broadcasting House, London in 1932. For the Underground Railways he made the figures of South Wind, North Wind and East Wind. These show his vigorous style with bold firm masses and powerfully rhythmic forms. In his 1923 war memorial for Leeds University he depicted Christ flourishing the scourge and driving the money changers from the Temple. The figures have a distinct contemporary symbolism and in his autobiography he says they represent "the ridding of Europe and the World from the stranglehold of finance, both national and international."28 He had originally hoped to use this subject for his commission for the League of Nations building in Geneva. He believed materialism and the money making motive were paramount in modern society and saw them as a force of evil, destroying true faith and values. This reveals the didactic and moral end of his art and it is in this respect that he can be compared to Katharine Maltwood. Both had their roots in the Arts and Crafts Movement and both represent different latter day manifestations of its ideal to reconcile modern art with modern life. The products of Morris and his associates had come to be appreciated only by an affluent and intellectual elite and thus their vision of a new society never came about. By the time of the First World War this failure of the Arts and Crafts Movement only served to emphasize the isolation of the artist craftsman and to set them apart from the rest of the community. In many respects this is what happened to both Eric Gill and Katharine Maltwood and they then sought different means to find an alternative solution. Gill explained his ideals and aims in a number of books such as Art Nonsense, 1929, Beauty Looks after herself, 1933, and Money and Morals, 1934. In the Arts and Crafts tradition he deplores the disappearance of the English craftsman and his engulfment as a mere machine minding hand in the lap of industry. While living from 1907-24 in a craft oriented commune in Ditching, Sussex, his aim became to reconcile modern art and life through a return to faith in God. His conversion to Roman Catholicism at this time was of particular significance to this aim. To Gill the exercise of his art became a religious activity. He wrote "The artist as prophet and seer, the artist as priest - art as man's act of collaboration with God in creating, art a ritual - these things 1 believed in very earnestly"29 Katharine Maltwood likewise believed there should be a rejection of the materialism of industrial society and a return to faith with art as an expression of God. However, while Gill turned to Roman Catholicism, she was, as we shall see, drawn to more esoteric faiths, and to Canada.

All content on this page is copyright © 30 January, 2006 |

||